Encountering Christ 50 years after Vatican II

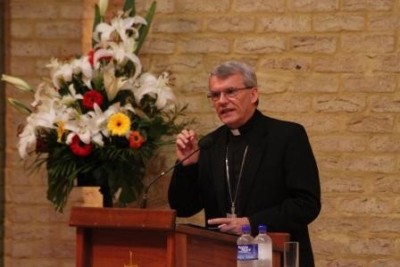

In the final lecture of an series celebrating the 50th anniversary of Vatican II, Archbishop Timothy Costelloe shares how "to encounter Christ is unambiguously and unapologetically a call to encounter him in and through the Church".

Encountering Christ – The Call of Vatican II

Celebrating 50 Years of Vatican II

Infant Jesus Parish Hall, Morley – Tuesday 24 October 2013

Introduction

Blessed John Henry Newman, widely regarded as a significant figure in the theological vision which was to inform the thinking of the bishops at the Second Vatican Council, was once criticised by a contemporary who suggested that his sermons, acclaimed though they were by so many, nevertheless showed what the critic saw as “a want of reverence” because they did not sufficiently mention Jesus Christ. In response Newman pointed out that the name of Jesus “occurs (after the salutation) once in James 1, once in James 11, and not in James 111 or 1V at all. Not once in 3 John” (Cooper, Newman, Spirituality, 93-94). Newman also defended himself against this charge by pointing out that “in the first three hundred pages of my last volume of Sermons I find his name occurs in more than 150 pages … often many times in one page” (Cooper, 94). Newman regarded the charge as a serious one and felt the need to defend himself partly by pointing out that even in some of the books of the New Testament itself Christ was not always explicitly mentioned. Newman’s inference, of course, is that Christ was at the very heart of the New Testament whether his name was explicitly mentioned or not.

I have not gone to the trouble of counting the number of times the name of Christ is mentioned in the sixteen documents of the Second Vatican Council. I presume there are more than 150, but I am happy to leave the laborious task of counting them to someone else. And certainly I do not want to suggest that the documents of Vatican 11 do not have Christ as their centre and their inspiration.

The reason I begin with this curious story about John Henry Newman is to simply to note the important point that while there is no one document from the Second Vatican Council which seeks to or claims to develop a systematic theology of Christ, what the scholars call a “Christology”, we must not too easily conclude that the Council was insufficiently focused on Christ as the centre of our faith. Nor however should we dismiss without any further investigation the suggestion that one of the areas under-developed in the documents of Vatican 11 is precisely a systematic and exhaustive treatment of the mystery of Christ.

Although I have not been able to conduct an exhaustive search, it does remain the case, however, that as far as I am aware there has not been a great deal of attention given to a study of the Christology of the Second Vatican Council. Certainly a wide variety of christologies have been offered by theologians since the Council, many of them based largely on some of the new methods of interpreting scripture which have emerged or become more widespread in the last fifty years. Whatever the relationship of these new christologies might be to the general theology of the Second Vatican Council, it seems that a close and detailed study of the specific Christology of the Council has not been undertaken. While I do not intend to develop such a study in this evening’s presentation I will inevitably be touching on what I judge to be some of the central Christological themes which emerge from the documents of the Second Vatican Council. Hopefully at some stage someone might indeed undertake a close study of the Christology which informs the documents of Vatican 11. I believe it would be a very useful addition to our theological understanding.

Encountering Christ – the Fundamental Question

As I reflect on the specific topic I have been asked to address this evening – Encountering Christ: the Call of Vatican 11 – it occurs to me that such a topic does presume, or at least imply, that there is a Christology, a particular theological understanding of the person and mission of Christ, which underpins the discussions, debates and eventual formation of documents which are the product of what has probably been the most significant ecclesial event for the Catholic Church in many hundreds of years.

If I am right, and such a presumed or implied Christology does lie behind the documents of Vatican 11, then an immediate question emerges. If Vatican 11 was and is a call to encounter Christ, who is this Christ whom we are called to encounter?

This question immediately takes us back to the gospels. It is the question Jesus himself asked and it is the question the Church, and in some sense the world, or large parts of it, has been asking ever since. Jesus, in the Synoptic tradition, asks the question this way: “Who do people say the Son of Man is?” The question is addressed to the disciples who respond by saying, “Some say he is John the Baptist, some Elijah, and others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” Then comes the key question. “But you, who do you say I am?” Peter, the leader of the disciples, speaks up. “You are the Christ, the Son of the Living God.” We all know the rest of the story. Jesus praises Peter for his answer, proclaims him the rock on which he will build his Church, and reminds him that his faith is a gift from God. But crucially Jesus then goes on to explain what being the Christ, the messiah, really means: that he was destined to go to Jerusalem and suffer grievously at the hands of the elders and chief priest and scribes, to be put to death and to be raised up on the third day. This is too much for Peter. All he can hear is the unthinkable suggestion that Jesus must suffer and die and he is unable to accept this. “Heaven preserve you Lord,” he says, “this must not happen to you.” And Jesus, who had previously praised Peter for his faith now chastises him and calls him an obstacle in his path.

There are two important and related points in this story which I would like to highlight as a backdrop to my reflections this evening.

The first is that it is possible to get Jesus wrong, as the crowds did, and that it is important to get Jesus right. Those who thought Jesus might be one of the prophets come back to life at least had understood that Jesus was an important man of God, as significant as any other of the prophets who had gone before him. They had recognised the hand of God at work in him and were open to listen to his word. But it seems that they were unable to go beyond the categories they already knew and were comfortable with. Their assessment of Jesus was, we might say, an understandable position to adopt and certainly better than nothing. But it wasn’t enough. God was doing something completely new in Jesus, and they were unable to recognise this. They were locked into their own limited vision.

The disciples, or at least their leader Peter, were able to see further. Because of a special gift of God’s revelation, Peter was able to affirm that Jesus was not just another great prophet, but indeed something much more. “You are the Christ, the Son of the Living God”. And Jesus reminds Peter, as indeed he might remind us, that “it was not flesh and blood that revealed this to you but my Father in heaven”. And this brings me to the second point I want to make. If the crowds, even though they recognised God at work in Jesus, nevertheless got him wrong, Peter, even though he had been given a gift of revelation by the Father, also got Jesus wrong. He understood that Jesus was the messiah, the Christ, but he wanted and needed Jesus to be a messiah according to Peter’s preconceived idea of what a messiah should be – and whatever that was, it did not include mistreatment, suffering and death. The frightening thing about Peter’s response was that he could be, if I may put it this way, one hundred percent right, and completely wrong, all at the same time.

The question then - Who do people say that I am and who do you say that I am? – is a vital one with which we have to take great care. We can so easily go astray. And so, we must be alive to the danger that in the end both the crowds and Peter, each in their own way, succumbed to. We must be careful not to bring our own presuppositions, and our own wishes, and our own preconceptions to the question of who Jesus really is. If there is a call in Vatican 11 to “encounter Christ” then it must be the real Christ we seek to encounter, not the Christ of our own making, the comfortable Christ who doesn’t challenge us to stretch our minds and our hearts.

Christ and the Church

Let me immediately put such a challenge before us by suggesting that for the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council one of the most fundamental beliefs which underpins their theological vision is the conviction that Christ is inseparably united to the Church. You cannot have Christ without his Church, and you will not encounter him, as he really is, independently of the Church.

At a time when we are all painfully conscious of the terrible pain and suffering which some in our Church have inflicted on innocent and vulnerable people, this is a challenging proposition, even an offensive one, for many. We might be tempted to echo the cry we hear, in one way or another, so often: yes to Christ, but no to the Church. Not long ago I was deeply saddened, but not really surprised, when a religious sister said to me that when she recites the Creed at Mass she can no longer bring herself to say she believes in the Holy Catholic Church. How can a Church which has caused so much suffering dare to refer to itself as holy?

The bishops at Vatican 11 were not naïve in this matter. In the document Gaudium et Spes, to which I will refer shortly, we read that “the Church is not blind to the discrepancy between the message it proclaims and the human weakness of those to whom the gospel has been entrusted … Guided by the Holy Spirit the Church ‘ceaselessly exhorts her children to purification and renewal so that the sign of Christ may shine more brightly over the face of the Church’ ” (GS 43). And speaking of the rise of modern atheism the bishops insist that “to the extent that they are careless about their instruction in the faith, or present its teaching falsely, or even fail in their religious, moral or social life, they must be said to conceal rather than to reveal the true nature of God and of religion” (GS 19). If this applies to the rise of atheism, how much more does it apply to people’s rejection of the Christian faith and the Catholic Church. It is to our shame that it has been those who are called to the ministers of Christ’s presence and grace in a particular way who have betrayed the Lord and his people, especially the most vulnerable – and in doing so have betrayed the Church as well. And yet, in spite of this terrible betrayal, we are still challenged to engage with the teaching of the Second Vatican Council that the call to encounter Christ is at the same time a call to engage with and in the Church. To encounter one is to encounter the other – and this remains true even if the Church’s leaders deny him, abandon him, or betray him.

Lumen Gentium and Gaudium et Spes

I would like to turn now quite explicitly to this theme of the relationship between Christ and the Church. As I pointed out earlier there is no single document among the documents of the Council which seeks to expound a developed and systematic Christology. We cannot say the same about the theme of the Church. While the Church’s understanding of Christ is scattered throughout the sixteen Council documents, the Church’s understanding of itself is far easier to uncover. It is significant that the two documents which are regarded by most people as the twin pillars of the Council’s work, Lumen Gentium and Gaudium et Spes, are known in English as the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church and the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World respectively. By their very titles, and then by their subject matter, they show that the central focus on the Council was the Church itself, either in terms of its own identity or in terms of its place and mission in the world.

Lumen Gentium, the Constitution on the Church, begins in this way:

Christ is the light of humanity; and it is, accordingly, the heartfelt desire of this sacred Council, being gathered together in the Holy Spirit, that, by proclaiming his Gospel to every creature, it may bring to all men that light of Christ which shines out visibly from the Church (LG 1).

Gaudium et spes, the Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, begins rather differently:

The joy and hope, the grief and anguish of the men and women of our time, especially of those who are poor or afflicted in any way, are the joy and hope, the grief and anguish, of the followers of Christ as well (GS 1).

In both cases, it is made very clear that the Church on which the Council wishes to reflect is intimately united to Christ.

We see this already in the preface of Gaudium et spes. Here the Council fathers explain that “the Council, as witness and guide to the faith of the whole people of God, gathered together by Christ” wishes to offer to the world “the light of the Gospel … and the saving resources which the Church has received from its founder under the promptings of the Holy Spirit (GS 3). In doing this “the Church is interested in one thing only – to carry on the work of Christ under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, for he came into the world to bear witness to the truth, to save and not to judge, to serve and not to be served” (GS 3).

This is an important aspect of the Council’s understanding of the Church: it exists in order to carry on the work of Christ, that is, to bear witness to the truth, to save and to serve. The Church then is about witness, about service and about salvation – but Gaudium et spes makes clear that this is only the case because Christ was about witness, about service and about salvation – and not only was, but still is – in and through the work of the Church.

It is interesting to note that the bishops, in producing Gaudium et spes, present the document as, in a certain sense, one of the fruits of their earlier work which produced the document on the Church; Lumen Gentium. Still in the preface of Gaudium et spes they offer the following remark:

Now that the Second Vatican Council has deeply studied the mystery of the Church, it resolutely addresses not only the sons (and daughters) of the Church and all who call upon the name of Christ but the whole of humanity as well (GS 2).

It is as if the Church, having reflected on its own true identity, feels emboldened to speak to the whole of humanity, to all of God’s children. I want to return to this idea shortly, because a later section of Gaudium et spes will give us an insight into one of the basic reasons why the Church feels able to do this, but first let us look briefly to Lumen Gentium. What is it about the Church’s self-understanding which gives it the confidence to speak to those who are not numbered among its members, or among the believers in Christ, or even believers in God?

The Church is in the Nature of a Sacrament

We have already considered the opening paragraph of Lumen Gentium. There Christ is proclaimed as the light of humanity and the Church as the reality from which that light shines out. This opening paragraph, which is absolutely fundamental for a proper understanding of the theological vision of the Council, goes on to make one of its most important and far-reaching statements:

Since the Church, in Christ, is in the nature of sacrament – a sign and instrument, that is, of communion with God and of unity among all men (people) – she here proposes, for the benefit of the faithful and of the whole world, to set forth, as clearly as possible, and in the tradition laid down by earlier Councils, her own nature and universal mission (LG 1).

It is important to notice that immediately after making this statement, the document then goes on to a presentation of what we might call salvation history. It starts with the creation of the universe and of humanity, “raised up to share in God’s own divine life”. It then goes on to speak of Christ the Redeemer and of those who would believe in him, those whom “he determined to call together in a holy Church”. The rest of this first chapter is a sustained reflection on the nature of the Church, drawing richly on biblical images. At the same time it is a detailed theological presentation of the person and mission of Christ. This mission is inextricably linked with the mission of the Church. For this reason we can say that chapter one of Lumen Gentium is a presentation of a Christological ecclesiology, and of an ecclesiogical Christology. This is not just a clever playing with theological jargon. It points to an absolute conviction of the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council – namely that it is impossible to separate the Church from Christ or Christ from the Church. Everything else the Council will say about the Church in this document, or indeed in any of the other documents, is grounded in this fundamental position. And it is, as I have suggested, both a foundational principle of ecclesiology and, very importantly, of the Council’s Christology.

It all derives, I suggest, from the opening statement that the Church, in Christ, is in the nature of sacrament.

The idea of a sacrament is in Catholic theology a very rich and very foundational one. For most of us to speak of sacraments is to bring to mind the seven sacraments we celebrate within our Church: Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Penance, Anointing of the Sick, Marriage, and Holy Orders. The older ones among us will remember the classic definition of a sacrament: a sacred sign which effects or brings about what it signifies. When water is poured over the head of a person being baptised and the baptismal formula is pronounced, the death to sin and rising to new life which the ritual signifies really does take place within the person. When the words of absolution are pronounced and the sign of the cross is made over the head of the penitent person, the forgiveness of sin which is signified really does occur. When the words of consecration are pronounced over the bread and wine by an ordained priest according to the requirements of the Church, Christ really does become present.

In Lumen Gentium the Fathers of the Council have taken the principle behind each of these sacramental celebrations and applied it to the Church itself. Just as the celebration of baptism both points to, and brings about, freedom from Original Sin, union with Christ in his death and resurrection and membership of his body the Church, and just as the laying on of hands and the prayer of consecration at an ordination ceremony both point to and bring about the inner enabling and empowering of a man for the responsibilities and duties of the priesthood, so the Church itself, in its very identity and ongoing existence in the world, both points to and brings about, in the words of Lumen Gentium, “communion with God and unity among all people”. It remains the case of course that just as a baptised person may seldom, or even never, make use of the grace of baptism, and just as an ordained priest may obscure, or even betray, the gift he has been given, so the members of the Church, individually or collectively, may constantly fail, even in drastic and destructive ways, to be what they are called and empowered to be. This is the great mystery and, in many cases the great tragedy, of the human dimension of the Church.

In terms of the foundational statement from Lumen Gentium which we are considering at the moment, that the Church is in the nature of sacrament, what is often not reflected on enough, I would argue, is the Council’s insistence that this is true only because the Church is “in Christ”. It is precisely this point that is spelt out in so much detail in the rest of the first chapter of the document. If indeed there is a Christology developed in any depth in the Council documents, then chapter one of Lumen Gentium is where it can be found. But it is a Christology which is at the same time a theology of the Church.

Not surprisingly this chapter relies very heavily on the scriptures to underline the importance of Christ and his relationship to the Church. For example the Fathers of the Council can say that “the Kingdom of God is revealed in the person of Christ himself” (LG 5) and at the same time that the Church is “the kingdom of Christ already present in mystery” (LG 3). They will also say that the Church “is she whom he (Christ) unites to himself by an unbreakable alliance” (LG 6) and they will reflect at some length on the Pauline image of the Church as the Body of Christ with Christ as the head. In paragraph eight they will insist that Christ “established and ever sustains here on earth his holy Church, the community of faith, hope and charity, as a visible organisation through which he communicates truth and grace to all men (people)” (LG 8).

Christ and the Church – Unity not Identity

In all of this the Council Fathers are spelling out what they mean when they say that the Church is, in Christ, in the nature of a sacrament. In the Catholic world view it makes no sense to speak of the Church as if it has some kind of existence apart from Christ. Catholic theology will not allow us to collapse the two and dissolve the distinction between Christ and the Church. The Church is not Christ and Christ is not the Church. But nor will Catholic theology allow us to separate Christ and his Church, any more than a body can be separated from its head, or a good and true shepherd from its flock, or a bride from her spouse. A shepherd without a flock is hardly a shepherd, a bride without a spouse is hardly a bride, and a body without a head is hardly a body, or at least not a living one. The Church is what it is because it is in Christ. And very significantly this is Christ’s doing before it is ours. The existence of the Church, its ongoing presence as sacrament in and to the world, is ultimately not dependent on us but rather totally dependent on Christ, who promised to be with his Church until the end of time. The images chosen to express this dependence of the Church on Christ - head, shepherd, spouse - are important. In the world view of the New Testament it is the head which gives life to the body; it is the shepherd who holds the flock together; and it is the spouse whose love draws the bride to himself. As the letter to Timothy reminds us, “we may be unfaithful but he is always faithful for he cannot disown his own self.”

It is because the Church is “in Christ” then that she is a sacrament, a sign and instrument, of communion with God and of unity among all people. These two aspects of the Church’s vocation, to be sign and instrument of communion with God and of unity among all human beings, are really the two dimensions of what it means to be saved. In John’s gospel, when Jesus speaks about the meaning of his death he says that “when I am lifted up from the earth I will draw all people to myself” (Jn …). He is referring of course to his death on the cross. In drawing all people to himself he is drawing them into communion, into oneness with him, but of course, in doing so, as he gathers them from the four corners of the earth to encounter him at the foot of the cross, they are all drawn closer to each other. The Church finds itself at the foot of the cross. Here Jesus gathers not a collection of individuals but a community. This is clear from the presence of the Mother of Jesus and the beloved Disciple. The dying Jesus gives them to each other, not just as an act of concern by a dying man for the well-being of his mother, but as an entrusting of each to the other so that they might form a new family: a family with faith, represented by the mother of Jesus, and discipleship, represented by the Beloved Disciple, as that which binds them together and makes them a family, a communion.

The Fathers of Vatican 11, having carefully considered this profound theology of salvation, will find it easy in later documents to simply say that the Church is the universal sacrament of salvation. It does so in Lumen Gentium 48, in Gaudium et Spes 45, and in Ad Gentes, the document on the Church’s Missionary Activity, in paragraph 1. The two latter instances, in fact, reference the statement made in Lumen Gentium.

It is important to note that in speaking of salvation as being constituted by communion with God and unity among all people, the Council Fathers are really directing us not just to the content of salvation but more foundationally to the saviour himself. One of the vital links which the theology of Vatican 11 makes is that between Christ as saviour, the Church as sacrament of salvation, and salvation as being about communion – with God and each other.

Salvation and Communion

When I was, as a young priest, a student of theology in Rome, I was fortunate to have as one of my professors and the supervisor of my thesis Fr Angelo Amato. He later became the Secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and is now the Cardinal Prefect for the Congregation of Saints. He taught us about the sacramental principle, that is, that God chooses to encounter us in and through the material realities of our world – water, bread, wine, oil, gestures, words and so on – and that this sacramental principle was really a playing out of a much more foundational principle, namely the incarnational principle. It is summed up beautifully in John’s Prologue: the Word became flesh and lived among us. This incarnational principle was and is, to quote Cardinal Amato, “God’s preferred methodology”. In seeking to encounter us God steps into our human story and becomes one of us in Jesus Christ. In this way the humanity of Jesus becomes the sacrament, the sign and instrument, of the deeper, in some ways hidden truth, of God present to us, God with us. In this mystery of the incarnation, we see realised the fullness of salvation – the communion between God and humanity, fully achieved in a unique way in Jesus who is both divine and human. Jesus himself is the sacrament - the sign, the instrument and the realisation - of communion between God and humanity. He is the sacrament of salvation – and it is only because the Church is in him that it can also be spoken of as the sacrament of salvation.

This is why the intimate and unbreakable communion between Christ and his Church is so vital. Through our Baptism first and foremost, and then through our reception of the sacraments of Confirmation and the Eucharist, we are not simply brought into a fellowship with other Christians, all on a journey towards our heavenly home. This is true of course, but there is much more than that. St Paul will speak of baptism as a dying and rising with Christ. He will remind us that we have all received the one Spirit and therefore belong to the one body. He will insist that as members of this one body, we have Christ as our head and the source of our life. And he will assure us that through our sharing in the Eucharist we though many are one body and that body is Christ.

He will tell us that we have put on Christ and that we are called to have in us the same mind that was in Christ. He will remind us that our true life in hidden with Christ in God and that, like him, we no longer live but it is Christ who lives in us. All of this points in one very clear direction. The mystery of our