POVERTY MIGRANTS & HOMELESSNESS REPORT: Poverty Case Study

Poverty and inequality are a global phenomenon, even in developed nations such as Australia. Photo: Supplied.

By Eric Martin

The recently released Poverty, Homelessness and Migrants in Western Australia, by the University of Notre Dame Australia, and commissioned by the Archdiocese of Perth is the first in a series of planned, annual research reports that will inform the provision of the Catholic Church’s social outreach programs in Perth.

The Record journalist Eric Martin takes a look at a real life situation of a Perth father who is experiencing poverty.

Wayne is a father with a four-year-old son and nearly every day he journeys into Northbridge by train to try and sell his artworks, just to get enough money for both of them to eat.

He is, like so many others, just one of the faces of the poverty that has become synonymous with the post-boom years.

“I’ve got this skill and it seems like the most positive way forward for me at the moment,” Wayne said.

“I’ve been out here for 18 months now and some days you sell some and others, it’s like nothing and no one is interested.”

“Yeah it’s hard. You know there’s begging and just asking and waiting for handouts but I’d rather be in here trying to sell something in exchange.”

Refusing to surrender to the situation, Wayne’s artwork represents hope for the future. Photo: Eric Martin.

The emotion in Wayne’s eyes as he shares his story is undeniable, especially when recounting the embarrassment and humility of being a father who is not able to feed his family.

“I travel in by train and spend most of the day here,” Wayne said. “It’s especially hard when the rangers keep moving me on, you know, I just want to be able to set up and sell my paintings, I’m not harassing anyone or causing a disturbance.”

He goes on to describe the difficulties that he experiences in trying to stay positive on a daily basis in the city and the frustration of trying to access help in a consistent and reliable way.

Steve McDermott, Director of Catholic Social Services Western Australia (CSSWA) is on the frontline for the battle against poverty. Photo: Eric Martin.

Wayne’s words echo those of Steve McDermott, Director of Catholic Social Services Western Australia (CSSWA) when describing the situation faced by many West Australians living in poverty.

“The fact is that a lot of families are exhausting themselves because they’ve got to go to all these different agencies, now not only is that time consuming but it’s extremely demoralising for a person to go to all these agencies, to explain the situation again and again and again,” Mr McDermott explained.

“How many times do you have to say “I’ve got no money?”

The excess of agencies is problematic for service providers as well who find it almost impossible to quantify the level or types of assistance being given in order to coordinate their efforts, due to the lack of transparency and inter-agency communication in the sector.

“You might be working for an agency that is dealing with a family and then I’m dealing with the same family, but from a different agency, with a different funding stream… So nobody knows where that money is going,” Mr McDermott said.

“And there’s a consequence because it gives lie to this idea that people are robbing the system, and that’s wrong.”

“What I want to return to again and again is communication,” Mr McDermott explained.

“That kind of thing is a direct consequence of a lack of communication and competitive tendering. The whole idea is to get people to jump through hoops for a miniscule amount of money, it makes them feel like little people, it makes them feel diminished, and it’s horrible.”

Mr McDermott’s sentiments were echoed by Wayne who went on to clarify the issues as experienced personally, highlighting the fact that because of the lack of communication between agencies, people’s trust in the system is being destroyed.

“I’ve been through so many different agencies,” Wayne said.

What is poverty?

“The poor you will always have with you,” are Jesus’ words to his disciples in Matthew 26 and in 2019 we can testify to the truth of this statement – by the end of 2018 there were an estimated 3.05 million Australians living in poverty (13.2 per cent of the population) according to Poverty, Homelessness and Migrants in Western Australia.

One in eight Australians experiences poverty on a daily basis and the terrifying reality is that this is actually an improvement on earlier statistics: “Poverty declined substantially from 13.1 per cent in 1999 to 11.5 per cent in 2003, then rose sharply during the boom years to 14.4 per cent in 2007.

In 2009, the poverty rate fell to 12.6 per cent before stabilising at 12.8 per cent in 2015”.

The Poverty, Homelessness and Migrants in Western Australia report is a collaborative research project between the Catholic Archdiocese of Perth and the University of Notre Dame Australia and is the first of a series of planned, annual research reports that will inform the provision of the Catholic Church’s social outreach programs in Perth.

The research’s aim is to enhance understanding of the locally specific variables that contribute to social and financial inequality in order to enhance the efficacy and effectiveness of fund allocation and decision-making processes.

Dr Martin Drum signs the collaborative research agreement between UNDA and the Archdiocese of Perth on 5 September 2018. Photo: Amy Gibbs/UNDA.

One of the most crucial aspects underpinning the study is the development of a Perth-specific definition of poverty, one that encapsulates the unique conditions facing people either in, or at risk of experiencing it.

“What defines a person as being in poverty?” asked Dr Martin Drum, Director of Public Policy and Associate Dean of Research (School of Arts and Sciences) at UNDA.

“Is this an absolute value representing the bare necessities needed by a family on any given week – Absolute Poverty? Or is it a relative value, one that depends on the level of wealth in the local area as a comparison point – Relative Poverty?”

This approach is already being advanced by initiatives such as “Registry Week”, a multi-agency effort that collects on the ground data on a series of nights in the Perth CBD and Fremantle.

By conducting an overnight count and interviewing consenting individuals living on the streets, valuable information is gathered about trends and reasons behind homelessness – the undeniable face of absolute poverty in Perth.

In 2016, when this survey was last conducted, 30 individuals in Fremantle were identified as having the greatest degree (acuity) of need due to a complex range of issues they faced including long term homelessness.

Though the existence of an absolute poverty line is undeniable (the inability of the individual in question to achieve the basic minimum requirements of life, such as food, shelter and clothing), a relative definition allows for a comparison of the quality of life experienced by those in poverty with the ‘average’ citizen.

Even Adam Smith, father of Economics and author of the historically significant The Wealth of Nations, famously said, “By necessities, I understand not only the commodities which are indispensably necessary for the support of life but whatever the custom of the country renders is indecent for creditable people, even of the lowest order, to be without.”

Differences in the definition of poverty and its contributing variables have a significant impact on the methodology of the scientists conducting research in the field.

For example, in this report relative poverty is defined as an income less than 50 per cent of the median average Australian wage, yet is compared to the 60 per cent median wage in order to demonstrate the impact that this can have on results.

For example, the rate of poverty experienced by older Australians (65+) is 43.5 per cent when the 50 per cent of median income poverty line is used and 64.9 per cent when the 60 per cent of median income poverty line is used.

Similarly, the profile of poverty by age shows that this age group makes up only 14.3 per cent of people in poverty if the 50 per cent of median income poverty line is used and 21.8 per cent if the 60 per cent line is used.

In terms of funding allocation and planning, this is a significant difference.

According to the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs – A hand up not a hand out: Renewing the fight against poverty (2004): “Poverty as a concept is difficult to define…there were differing views amongst participants as to what constitutes poverty or how best to measure it (a problem shared with academic researchers and the community generally)”.

“One study has argued that the only point of general agreement is that people who live in poverty must live in a state of deprivation, a condition in which their standard of living falls below some minimum acceptable standard.”

The majority of Australian poverty research defines poverty in terms of income inadequacy and utilises a specific poverty standard – The Henderson Poverty Line.

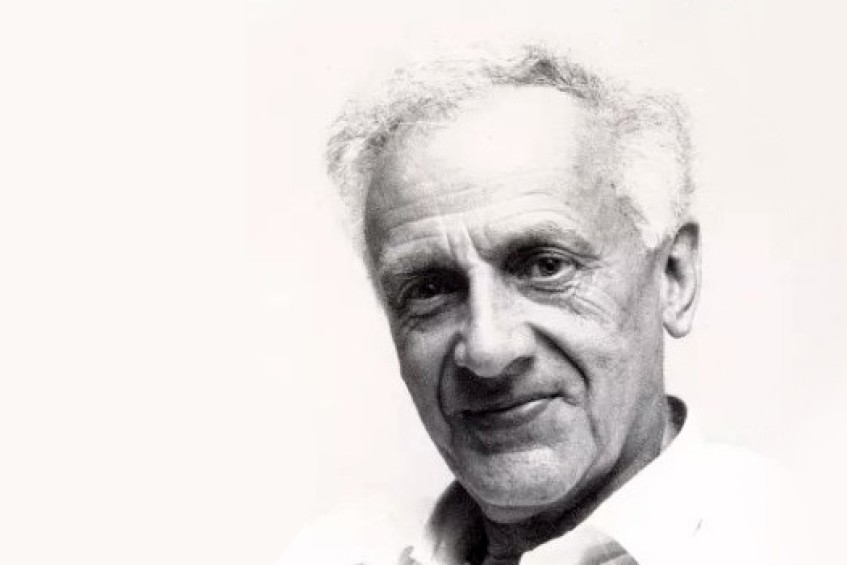

Prof Ronald Henderson is the man responsible for the Henderson Poverty Line, the standard measure of poverty used by the ABS since 1973. Photo: Supplied.

Named after the Chairman of the Commission of Inquiry into Poverty (1966), Professor Ronald Henderson, the measure was first used in a study of poverty in Melbourne in 1966 and was adopted as the standard measure of Poverty by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 1973.

The Henderson Poverty Line has come under fire by many critics who question the model’s relevance today, citing the fact that it is now over 50 years old and includes research carried out in New York, USA, in the 1950’s – the basis for equivalencies used to calculate budget standards, housing costs, etc.

Using the Henderson Model assumes that the relative expenditure patterns and needs of Australian families are currently the same as those derived for New York families in the early 1950s.

“This type of data set within the modelling demonstrates the need for and importance of engaging in research in this field,” Dr Drum said.

“We need to ensure that our understanding of the issues that lead to and keep people homelessness accurately reflects reality, here on the streets of Perth.”